Statistics have long been signaling the rise in obesity across the world. If asked what is the reason behind this upsurge, chances are that we would all point towards increased calorie consumption, sedentary lifestyle and eliminating balanced meals from our daily diet. Statistical materials issued by renowned agencies are usually the most credible tools to gauge a particular variable. However, a thorough analysis of the information over a period of time is essential to draw a conclusion. When three scholars set out to analyse the nutritional trends in India spanning between two decades, the results revealed a fundamental flaw.

When statistics point at a considerable increase in the rate of obesity (or a certain variable like calorie intake, diabetes and others) in a given year with respect to the last five years, does it really mean that the variable rate is on the rise? Not necessarily. This is exactly what happened when Nidhi Kaicker, Assistant Professor, Ambedkar University, Delhi; Vani S Kulkarni, Department of Sociology, University of Pennsylvania; and Raghav Gaiha, Harvard School of Public Health; decided to delve deeper into the science behind studying statistical data better.

In their combined endevour, published in one of the leading news dailies, the trio brought to light some facts that redefine the way we view statistical truth. They reviewed the data published by the National Sample Survey. Nutritional markers such as protein, calorie consumption and fat intake by the rural and the urban population were taken into account for the year 1994, 2005 and 2012 respectively. The results were surprising.

According to the team, most variables – like calorie intake and fat consumption – witnessed growth after the year 2005, especially in 2011-12. Yet the team concluded by stating that the overall calorie intake was on a decline, despite the values in the year 2011/12 being “slightly higher” than those during 2004/05. Interestingly, when the data was compared across the years – from 1994 to 2012 – it was found that despite an increase in the year 2011/12, the overall trend for calorie intake was on a decline, therefore “there was no reversal” in the trend.

It was also found that the proportion of rural undernourished poor to the poor population, has been steadily increasing – 74% in the year 1994, which rose to 84% in the year 2004/05, and remained unchanged during 2011/12. This can be viewed in correlation to the decline in the average protein intake by the poor – which remained unchanged during 2005-2012 but saw an overall low for the period 1994-2012.

The above examples offer the insight that short term ebbs and lows are not helpful in predicting a wider trend, which can only be achieved by taking widespread averages into account.

Another nutritional marker studied was the growth rate of fat intake 1994 onward. The NSS report suggested a steady increase in fat consumption, both by the urban as well as the rural population in the past two decades. However, the increase was sharper during 2005-2012 as compared to 1994-2005.

The Triggers

While most of us blame inactive lifestyle and increased consumption of processed foods, not many understand the concept of ‘diet diversification’. The authors point at the rapid diversification of Indian diet and various other contributing factors.

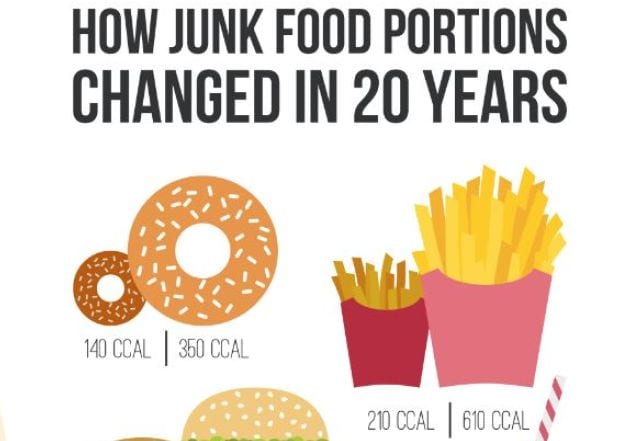

Diet diversification refers to a move away from staples towards meals that are loaded withprocessed items. The experts saw this as a play of demand and supply. Here, demand rests on purchasing power. While people with money and affluence don’t mind shelling out more, “smaller and poorer households are more dependent on street food,” the experts noted. There is also a noticeable increase in the number of supermarkets and fast food outlets as well as the number of companies selling sugary beverages. Dietary shifts therefore reflect the correlation between these demand and supply factors. As more and more consumers prefer supermarkets with easy availability of imported food items, the local food mechanism suffers, affecting producers, suppliers, distributors and others in the chain.

Despite all this, when one turns to proofs or data and statistical truths, it is documented that, “diet became more diversified during 1994-2005,” with a subtle slump recently during 2005-12. The experts therefore press for a point – trends are easy to formulate taking into consideration averages obtained from a smaller time span. Interestingly, the entire picture changes when the same variable is studied taking a longer period into account. It is difficult and impractical to measure consistency, slump or a jump while looking at short term information. The NNS report, when studied in depth, proposed “negative association between calorie intake, protein intake and diet diversification,” which to the common mind, would come as a surprise.

“Whether the weakening of diet diversification, especially among the affluent, is in part a reflection of growing awareness of the benefits of a healthier diet, is plausible. But this needs validation,” concluded the team.

Source: ‘Chew on These Averages’, The Economic Times

[“source-ndtv”]