Space environment around Pluto and its moons is almost empty, containing only about six dust particles per cubic mile, according to data collected by a student-built instrument riding on Nasa’s New Horizons spacecraft.

The spacecraft found only a handful of dust grains, the building blocks of planets, when it whipped by Pluto at about 49,000 kilometres per hour July last year, scientists said.

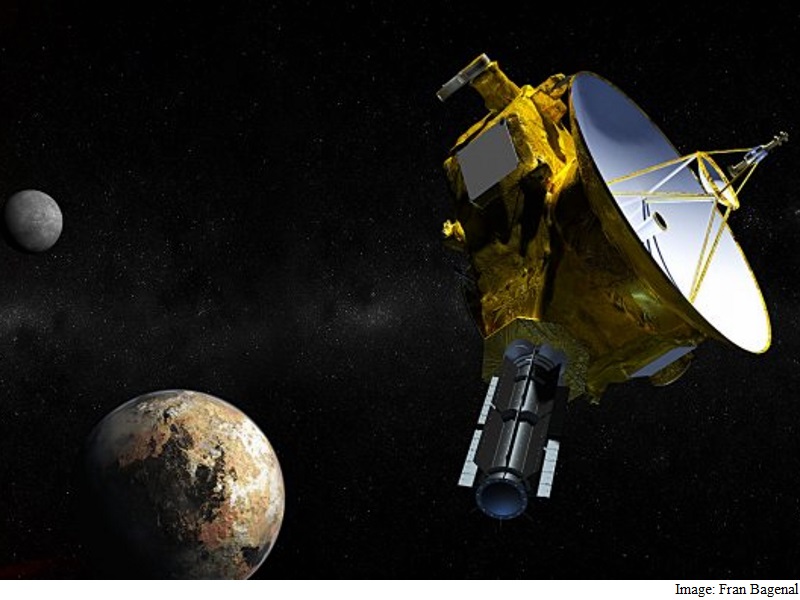

“The bottom line is that space is mostly empty,” said Fran Bagenal, a professor at University of Colorado Boulder, who leads the New Horizons Particles and Plasma Team.

“Any debris created when Pluto’s moons were captured or created during impacts has long since been removed by planetary processes,” said Bagenal, a faculty member at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP).

Studying the microscopic dust grains can give researchers clues about how the solar system was formed billions of years ago and how it works today, providing information on planets, moons and comets, said Bagenal.

Launched in 2006, the New Horizons mission was designed to help scientists better understand the icy world at the edge of our solar system, including Pluto and the Kuiper Belt.

A vast region thought to span more than a billion miles beyond Neptune’s orbit, the Kuiper Belt is believed to harbour at least 70,000 objects more than 96 kilometres in diameter and contain samples of ancient material created during the solar system’s violent formation some 4.5 billion years ago.

The Student Dust Counter (SDC) logged thousands of dust grain hits over the spacecraft’s nine year, 3 billion-mile journey to Pluto while most of other six instruments slept, said Professor Mihaly Horanyi from LASP.

“Now we are starting to see a slow but steady increase in the impact rate of larger particles, possibly indicating that we already have entered the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt,” said Horanyi, the principal investigator for the SDC.

The dust counter is a thin film resting on a honeycombed aluminium structure the size of a cake pan mounted on the spacecraft’s exterior.

A small electronic box functions as the instrument’s “brain” to assess each individual dust particle that strikes the detector, allowing the students to infer the mass of each particle.

“Our instrument has been soaring through our solar system’s dust disk and gathering data since launch,” said Jamey Szalay, a former CU-Boulder student, now postdoctoral researcher at Southwest Research Institute (SwRI).

“It’s going to be very exciting to get into the Kuiper Belt and see what we find there,” said Szalay.

The research was published in the journal Science.

Download the Gadgets 360 app for Android and iOS to stay up to date with the latest tech news, product reviews, and exclusive deals on the popular mobiles.