Scientists are tracking the effects of a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet for its potential to starve brain tumours and treat cancer patients.

The ketogenic diet was developed in the 1920s to help people with epilepsy. It works by forcing the body to burn fats rather than carbohydrates. Normally, the body converts carbohydrates into glucose. But a low-carbohydrate diet causes the body to convert fat into fatty acids and ketone bodies; the latter acts as a replacement for glucose. High levels of ketone bodies are associated with reduced seizure frequency.

It is theorized that the ketogenic diet could be used to starve off some forms of cancer. Cancer cells use to glucose to grow, and they’re inefficient at using ketone bodies for energy

So far, the diet’s effects on cancer cells has only been tried on animals and noted only anecdotally in human cases. A 2012 study on mice, found that ketogenic diet “significantly enhances” the anti-tumour effect of radiation.

Dr. Jong Rho, head of pediatric neurology at the Alberta Children’s Hospital, previously used the diet to treat patients with epilepsy and was part of the 2012 study.

Rho has also been monitoring the case of 15-year-old Adam Sorenson.

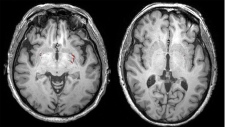

More than two years ago, the Calgary teen was diagnosed with stage four glioblastoma multiforme, the most common and aggressive form of brain cancer. The average time of survival after diagnosis is 12 to 15 months.

Following Adam’s diagnosis, doctors performed surgery to remove a baseball-sized brain tumour.

Sorenson then received radiation treatment. Chemotherapy was an option, but tests suggested he might not benefit.

With few options left on the table and a real chance the cancer would return, Sorenson’s parents did some research and put their son on the ketogenic diet.

“You feel pretty helpless as a parent,” said Brad Sorenson, Adam’s father.

“You are waiting for the tumour to reappear and that is when I thought, ‘What can I control? What can I do?’ And I started looking into diet.”

With little to lose, Sorenson’s parents hired a dietician to make a food plan. The goal was to make his diet 80 per cent fat, 15 per cent protein and five per cent carbs.

“Do you prefer to not eat candy or survive cancer? I prefer to do whatever it takes to stay alive,” Adam said.

The teen has been on the diet for two and a half years. His most recent brain scan in March was clean, despite the fact that his type of cancer usually recurs within 18 months.

Rho is intrigued but remains cautious about the results.

“Adam has done quite well,” said Rho. “We have been following him every several months to make sure there isn’t a recurrence of the cancer.”

“If you were to meet him on the street you would never know he had the diagnosis to begin with.”

And Rho cautions patients against trying the diet on their own.

“We certainly don’t want to communicate to families that diet is a replacement to existing therapies – it is not,” he said.

“It could be an adjunctive treatment in patients who have various forms of cancer. (They) should adopt current standards of care which involve a combination of surgery, chemotherapy radiation.”

Traditional treatments for brain cancer include: neurosurgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Despite these efforts, the survival rate for some brain tumours ranges between eight months to less than two years.

Rho said research on dietary treatments has been neglected over the years, so there is a need for further study to determine whether they can be an effective way to manage or cure cancer.

“While the anecdotal evidence is quite compelling, obviously we need more rigorous and controlled studies to find out if diet can be an effective option for patients with various forms of cancer,” he said.

In light of Sorenson’s recovery, his father has become an advocate for more research on the treatment.

“Nobody survives. There is no hope with this disease, and so I get calls from people who are trying and failing and get desperate,” said Brad Sorenson, adding he doesn’t want to give people “false hope that this diet will pull people back from the brink.”

There is also more evidence potentially on the horizon.

Researchers in Phoenix, Ariz., are hoping to put 80 patients with metastatic brain cancer on the ketogenic diet, in addition to chemotherapy and radiation, and track their progress.

“The beauty of this the ketogenic diet has been used for a very long time to treat epilepsy, especially kids who don’t respond to medication,” said Adrienne Scheck, professor of neurobiology at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix.

But getting funding for the treatment has been a challenge.

“There is no financial incentive. There is no drug company that will help support this, so getting it funded is difficult,” said Scheck.

Scientists from around the world are also set to gather in Banff this fall for the Global Symposium on Ketogenic Therapies.

[“source-ndtv”]