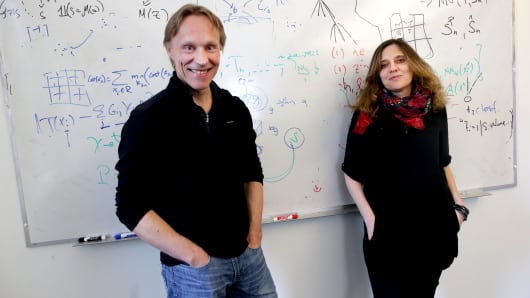

Regina Barzilay teaches computers how to learn. A professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, her work focused on natural language processing – training computers to understand human speech – until a breast cancer diagnosis three years ago.

“Going through it, I realized that today we have more sophisticated technology to select your shoes on Amazon than to adjust treatments for cancer patients,” Barzilay said in an interview at her office in Cambridge. “I really wanted to make sure that the expertise we have would be used for helping people.”

Barzilay’s group, in collaboration with Massachusetts General Hospital, is now applying their expertise in artificial intelligence and machine learning to improve cancer diagnosis and treatment. They’re asking questions like whether computers can detect signs of breast cancer in mammograms earlier than humans are currently capable of, and whether machine learning can enable doctors to use all the huge quantities of data available on patients to make more personalized treatment decisions.

It’s a field some say is on the cusp of changing medicine.

“The potential is perhaps the biggest in any type of technology we’ve ever had in the field of medicine,” said Dr. Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Translational Science Institute. “Computing capability can transcend what a human being could ever do in their lifetime.”

Investment is pouring in, from tech giants like IBM’s Watson, Alphabetand Philips, to pharmaceutical companies and swiftly proliferating startups. The market for artificial intelligence in health care and the life sciences is projected to grow by 40 percent a year, to $6.6 billion in 2021, according to estimates from Frost & Sullivan.

Some of the earliest applications are expected to be in diagnosing disease. For Barzilay, the ability of computers to scour images holds the potential of earlier detection. She had been getting mammograms for more than two years before she was diagnosed at age 43.

“Looking back, there was clearly no tumor on the previous mammograms, but was there something in these very complex images that would hint at… a wrong development?” Barzilay asked. “It clearly didn’t just appear. Biological processes are in place to make a successful growth and it clearly impacts the tissue. So for a human who looks at it, it’s very hard to quantify the change, but a machine may look at millions of these images. This should really help them to look at these signs.”

Dr. Andy Beck, a pathologist at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Aditya Khosla, a computer scientist trained at MIT and Caltech, are tackling cancer diagnosis through images as well. They’re training computers to scour digital slides, and learn how to differentiate cells that are cancerous from those that aren’t.

They formed a startup, PathAI, last year after their technology won a competition in detecting breast cancer.

In the April 2016 challenge, an expert pathologist, charged with the same task as the computational teams, achieved an error rate of about 3.5 percent, Beck explained from PathAI’s headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Their team had an error rate closer to 7.5 percent, the best in the competition.

What was most interesting, Beck said, was putting the computer and pathologist together.

“The combination of human plus AI in this example reduced the expert’s error rate by 85 percent,” Beck said. “That was a really exciting finding.”

And because these trained computers get smarter with the more data they take in, the PathAI team’s technology improved over time. By November, Beck and Khosla’s system had surpassed the human expert.

Researchers are also using machine learning to make connections in data that people may not see. Joel Dudley’s team at Mt. Sinai in New York developed a system known as Deep Patient, scouring de-identified health data across the hospital system and combining information in multitudes of ways.

“One of the powerful aspects of deep learning is unsupervised feature learning,” Dudley explained, “meaning you don’t have to constrain upfront what you think is important for predicting something or modeling something.”

A physician or researcher focusing on type 2 diabetes, for example, may develop a model focusing on blood glucose or weight to try to predict who may be at risk for disease.

“But that then ignores all the other information in the health record that could be useful for predicting someone who’s at risk,” Dudley said. “So we use a deep learning approach where we could just pour in all the information we have on 5 million patients in our health system, from any test that’s ever been run on a patient.”

In results published last year in the journal Nature, Dudley’s team showed Deep Patient improved prediction of diseases from schizophrenia to cancer to severe diabetes.

MIT’s Barzilay was frustrated by medicine’s unsophisticated models as well. When she was going through treatment for breast cancer, she had questions about outcomes for different medicines for patients like her.

“They had this study which was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, and the number of women like me was very, very small,” Barzilay recounted. “I was really unable to get an answer for this data, and what I learned later was that most of the treatment decisions in this country are based on clinical studies. How come we’re not using all this data of what happened to people afterward?”

That’s another problem she set out to solve, using her expertise in natural language processing to teach computers to read health records. In both projects, Barzilay and her collaborators say they’re making progress.

“We rapidly moved into the big question, which is: ‘Can machines read mammograms?’ And I think they can,” Dr. Constance Lehman, a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School and chief of breast imaging at Mass General. “They will open up a whole revolution in health care.”

The applications of artificial intelligence in medicine span to consumer health as well. Philips, which is partnered with PathAI in improving cancer diagnosis, also sees the potential for data from wearables and smart toothbrushes to improve health care wherever we are.

“Sensor technology will pick up a lot of personalized data and that can be used to make personalized treatment plans,” Philips CEO Frans Van Houten said. “It will help do diagnosis better, and through artificial intelligence and machine learning we can take these massive amounts of data and interpret what is going on and then get to the first and right treatment.”

Skepticism, though, abounds, and there’s no lack of hype around AI.

“There’s no question that we’re perhaps at peak hype cycle right now,” said Topol.

The technology is still being validated, and challenges, including cost, access to data, and simply understanding how computers reach conclusions, abound.

“But if this plays out as it could,” Topol said, “it would probably be the most transformative impact that we’ve seen in the medical profession.”

[Source”timesofindia”]