Kabul-Mohammed Javed, lost both legs to a landmine when he was on an afghan army patrol.

But when he stands, strapping himself into plastic supports and steel leg posts and pulling himself erect between two exercise bars, there is a gleam of triumph in his eyes.

For a moment, he looks like the soldier he once was.

Afghanistan has been at war for a long time, long enough to produce three generations of battlefield victims. Thousands of them have lost limbs, mostly to Soviet-made land mines and other explosive devices.

Older military amputees are a familiar sight on the streets, begging on crutches at traffic intersections or holding up strings of cellphone cards on handless arms. A few push themselves about on low wooden dollies, grabbing at pedestrians’ hands and asking for change.

But the past decade of war against the Taliban has produced a new generation of disabled men, almost all still in their 20s. Many were injured during fighting in places such as Kunduz and Helmand provinces, which are in the news as targets of renewed Taliban offensives.

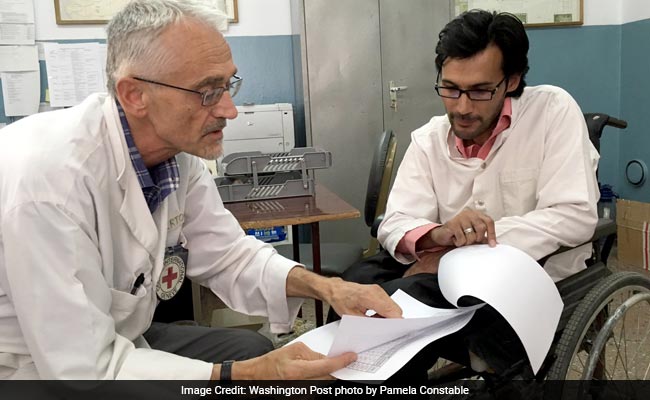

Dr. Alberto Cairo has helped Afghan war victims with amputated limbs since 1988.

And most are far more grievously wounded than the older veterans, because the explosive devices used by today’s insurgents are much more powerful.

“We used to see a lot of patients with one leg amputated. Now we see many with both gone. And they are so young,” said Alberto Cairo, an Italian doctor who has been working with disabled war victims here since 1988. He now heads the orthopedic program at a Kabul hospital run by the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Since he began his work 26 years ago, during the Afghan-Soviet war, Cairo has assisted more than 12,000 soldiers and police with amputations. Last year, his program helped 275 amputees from the security forces, providing them with 945 prostheses.

Every day, ambulances from Kabul’s military and police hospitals deliver patients to Cairo’s program, where they do exercises, practice using artificial arms and legs, receive counseling on social reintegration, and learn to play wheelchair basketball.

Mahmoodi, 26, is one of them. He lost both legs in a land-mine explosion in Kunduz a year ago, when the strategic northern city was briefly captured by the Taliban. It has been under a new insurgent assault since Monday.

“We retook the city, but the Taliban had planted mines,” he recounted. During a patrol he stepped on one, shattering his legs, and was rushed still conscious to a hospital run by Doctors Without Borders. Shortly after he was evacuated to Kabul, that hospital was mistakenly bombed by a U.S. warplane, killing 42 patients and staff.

Mahmoodi, sitting in a room full of sad-looking young men in wheelchairs one recent day, was not eager to talk at first. But he brightened up when a therapist suggested he demonstrate his new prostheses. He struggled into the complicated supports and heaved himself up. Suddenly, he seemed very tall.

“I sacrificed for my country,” he said. “Now I come here every day and I am trying to get strong again. I want to learn a skill. I want to stand on my own feet.”

Cairo said he and his staff avoid asking their patients too many nonmedical questions, because Afghanistan’s conflicts have been murky and politicized, and they don’t want to scare away former combatants from seeking help, no matter what side they were fighting for.

“We do not investigate. Anyone is welcome,” said Cairo, a rare Westerner who has stayed here through three wars. “We have had ex-Taliban, ex-mujahideen, new police and soldiers – all sitting on the same bench. And we have never had a single incident.”

In another room lay Mohammed Ezmatullah, 24, paralyzed by a bullet in the spine and sunk in gloom as he contemplated never being able to walk again. A border police officer, he was shot last spring during a firefight with the Taliban in Khanshin, a volatile border district in Helmand that was overrun by insurgents again last week.

“I feel weak and sad, but my real worry is my family,” he said, explaining that his salary of about $200 a month was the only income for his family of 12. “The ministry told me they will keep paying me for 10 months, and it is almost up. I served for seven years, and I hope they don’t forget me.”

Many of these young, severely disabled vets end up living at home, isolated and idle, unacceptable as prospective sons-in-law and dependent on their brothers or parents for nursing care, feeding and dressing. Nevertheless, a few seem to have found a purpose in life.

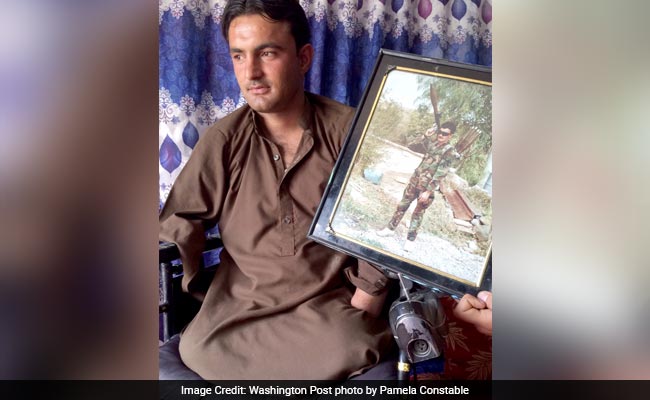

One is Mohammed Javed, 26, a former soldier who lost both legs and parts of both arms to an explosive device during a patrol in Helmand in 2013. He received extensive medical care through the Afghan and U.S. military, but he was never fitted with artificial limbs. He lives with his family in a poor section of the capital, where he powers through the dirt alleys in a motorized wheelchair.

“I used to be much taller,” he said one recent day at home, grinning wryly as he sipped water from a cup his brother held. He pointed to a photo on the wall, taken in a dusty village. It showed a swaggering young man in uniform, wearing dark glasses and carrying a rocket launcher on his back.

“That was my last mission,” he said.

These days he has a new one, crossing the city in his wheelchair to the Ministry of Defense and sitting outside a gate for hours, carrying a petition and telling anyone who asks that the government should do more for him and other disabled veterans. Under army policy, Javed still earns half-pay at $120 a month and was awarded a piece of land, but he still thinks it’s not enough.

“I don’t regret what I did for my country, but I’m disappointed,” he said. “I don’t want to be a burden. Sometimes when people see me, it ruins their day. But there are so many guys I fought with who were injured, too, some even worse than me. I try to look on the good side. At least I’m not a beggar.”

© 2016 The Washington Post